A healthy relationship with risk starts with understanding that downturns aren’t always as shallow and recoveries not always as swift as we’ve seen over the last 15 years or so. Three essential principles for dealing with risk can improve outcomes even if the ride gets wilder.

Principle 1: Be humble in the face of unknowable risk

The late financial historian Peter Bernstein once observed that certain risks are inherently unknowable ahead of time. These risks tend to be the most disruptive, having the potential to befall investors without warning. For example, a key factor in the 2008 global financial crisis that became clear only with the benefit of hindsight was the amount of systemic risk that had built up via credit derivatives. The degree to which risk-taking on credit—mortgage and corporate—was concentrated within the system was not well understood until the crisis deepened. This uncertainty drove the panic that set in at the height of the crisis.

“Equity market drawdowns can run longer and deeper than we’ve become accustomed to. It’s that potentially changing landscape that investors may want to prepare for.”

Kevin Khang, Vanguard Senior International Economist

In a similar vein, what alarmed the market about the recent tariff announcements was not that new tariff policies were being pursued. Rather, it was the magnitude and scope of these policies, and the pace at which they unfolded, that had been largely unknowable and exacerbated the volatility.

Truly disruptive risk is often unknowable ahead of time. Humility regarding this truth can help investors maintain a healthy perception of risk. Accepting that unknowable risks periodically roil markets can foster a flexible and measured response when tail risks—or extreme market developments—emerge, mitigating the impact of unforeseen events and preventing panic-driven decisions.

Principle 2: Have a robust asset allocation

Because the future is uncertain, and some risks are unknowable, it makes sense to find a robust solution—one that provides results that are good enough across a range of circumstances, rather than optimal under some scenarios but highly undesirable under others. More than being balanced by some combination of stocks, bonds, and cash and diversified within each asset class, a robust portfolio is one the investor can maintain, especially in extreme market conditions.1

Rigorous capital market return projections that consider the extremes are also critical to robustness. That’s because poor long-term results are a greater risk than short-term volatility for long-term investors. In practice, a robust approach to portfolio construction considers a diverse range of return environments over the investor’s investment horizon and achieves an allocation that would be suitable across these environments.

A new book by Joe Davis, Vanguard global chief economist, provides an example of such an approach for investors with seven- to 10-year horizons. Placing the odds of the economic environment fundamentally changing over the next decade at above 80%, this approach weighs two starkly different return environments. The resulting portfolio is robust for both: 1) an optimistic environment in which AI-driven productivity drives high economic growth and market valuations; and 2) a pessimistic environment where increasing structural deficits put upward pressure on inflation and yields, while pulling down equity valuations.

Principle 3: Be optimistic but prepared for downturns

Balanced investors must thoughtfully manage downside risk. Sticking with an allocation during significant drawdowns requires realistic expectations about one’s tolerance for pain. In today's market, this means having realistic expectations about potential drawdowns and not relying on overly optimistic return expectations based on recent performance.

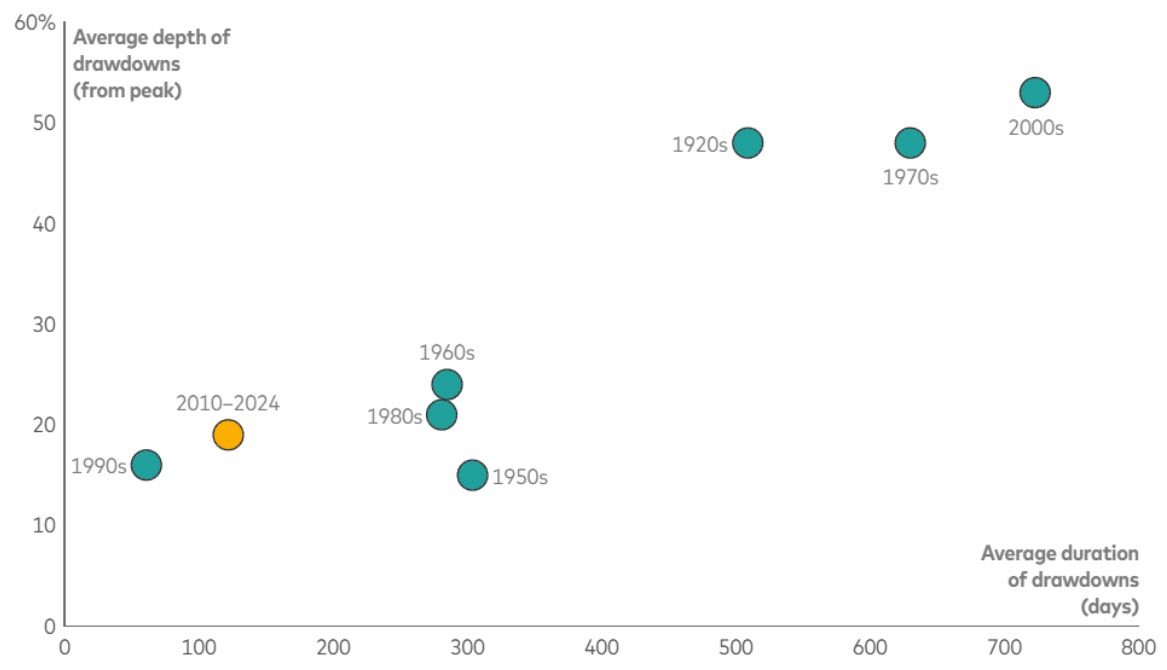

Mild stock-price corrections of recent years could give way to deeper, longer-lasting declines

Notes: Each dot represents the average duration and magnitude of all drawdowns greater than 10% observed during the respective period. Periods are decades, with two exceptions: The 1920s start on December 31, 1927, and 2010–2024 captures the 15-year period starting on January 4, 2010, and ending on December 31, 2024. Durations reflect the number of trading days from market peaks through troughs; in calendar terms, they would be longer. Percentages reflect price-only declines in the level of the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index (or the S&P 90 Index prior to April 1957); they ignore dividend payments. Dots for the 1930s and 1940s are not shown because the recovery from the last drawdown of the 1920s took over two decades to reach the level of the prior peak, which was established on the eve of the stock market crash of 1929. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. The performance of an index is not an exact representation of any particular investment, as you cannot invest directly in an index.

Sources: Vanguard calculations, based on index returns from Bloomberg.

As the figure shows, the last 15 years have been favorable for U.S. equities, with shallow and short-lived drawdowns. Some investors may be tempted to look back over this period—which they consider to be “long”—and surmise that such relative market tranquility is here to stay. The quick snapback from the sharp declines after the broad U.S. tariff announcements on April 2 may only reinforce such a stance. But as we can see from previous decades, equity market drawdowns can run longer and deeper than we’ve become accustomed to recently. Looking forward, it’s that potentially changing landscape that investors may want to prepare for.

Feeling our way toward sources of future risk—and potentially recalibrating expectations

The confluence of forces that led to subdued downsides in the last 15 years may be evolving, creating a more challenging risk backdrop:

- A renewed focus on fiscal responsibility may imply a reduced scope for fiscal stimulus in future economic downturns.

- Adverse supply-side developments and the potential for stagflation might limit efforts by central banks to mitigate market volatility.

- The prospect of a rearranged global trading ecosystem has a wide range of significant long-term implications that could create sources of disruption—many of which are unknowable.

For some investors, prudent risk management might mean recalibrating expectations to include deeper and longer-lasting drawdowns that are more in line with previous historical periods. Even if this recalibration doesn’t change one’s asset allocation dramatically, it may increase the odds of the investor maintaining their allocation during downturns.

Notes:

- All investing is subject to risk, includi the possible loss of the money you invest. Be aware that fluctuations in the financial markets and other factors may cause declines in the value of your account. There is no guarantee that any particular asset allocation or mix of funds will meet your investment objectives or provide you with a given level of income. Diversification does not ensure a profit or protect against a loss.

- Bond funds are subject to the risk that an issuer will fail to make payments on time, and that bond prices will decline because of rising interest rates or negative perceptions of an issuer’s ability to make payments.

- Bloomberg® and Bloomberg Indexes mentioned herein are service marks of Bloomberg Finance LP and its affiliates, including Bloomberg Index Services Limited (“BISL”), the administrator of the index (collectively, “Bloomberg”) and have been licensed for use for certain purposes by Vanguard. Bloomberg is not affiliated with Vanguard and Bloomberg does not approve, endorse, review, or recommend the Financial Products included in this document. Bloomberg does not guarantee the timeliness, accurateness or completeness of any data or information related to the Financial Products included in this document.

- Vanguard Mexico is not responsible for and does not prepare, edit, or endorse the content, advertising, products, or other materials on or available from any website owned or operated by a third party that may be linked to this email/document via hyperlink. The fact that Vanguard Mexico has provided a link to a third party's website does not constitute an implicit or explicit endorsement, authorization, sponsorship, or affiliation by Vanguard with respect to such website, its content, its owners, providers, or services. You shall use any such third-party content at your own risk and Vanguard Mexico is not liable for any loss or damage that you may suffer by using third party websites or any content, advertising, products, or other materials in connection therewith.

1 Some investors may wonder what’s wrong with adjusting their allocations on the fly, based on changed perceptions of risk. In some cases, the answer may be “nothing.” But such cases are likely limited to instances where market volatility has convinced the investor or their advisor that they previously over- or underestimated their risk tolerance—and that a new target mix of assets would be better for the long haul. Otherwise, Vanguard research suggests that an annual rebalancing strategy is optimal for investors who do not harvest losses for tax purposes or seek to track a benchmark. For more information, see Yu Zhang et al., Rational Rebalancing: An Analytical Approach to Multiasset Portfolio Rebalancing Decisions and Insights, Vanguard, 2022; available at corporate.vanguard.com/content/dam/corp/research/pdf/rational_rebalancing_analytical_approach_to_multiasset_portfolio_rebalancing.pdf.